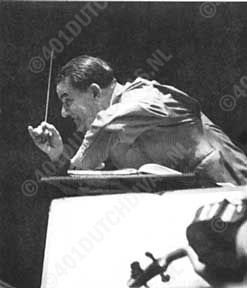

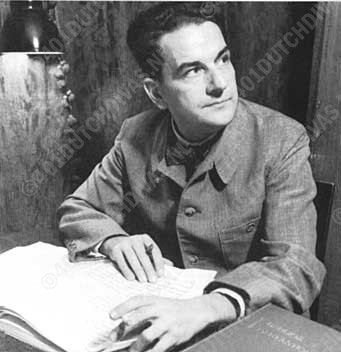

Eduard van Beinum Biography 1900-1945

source: Eduard van Beinum, the radio recordings. Q Disc 97015. Kees Wisse

Among the few childhood memories Eduard van Beinum could be drawn to recount in interviews was the following: As a fourteen-year-old in the town of Arnhem he had heard the Concertgebouw Orchestra play under its conductor Willem Mengelberg. The experience had completely overwhelmed him and he afterwards told his mother: "You will see the day when I shall be conducting this orchestra. At the time young Eduard could not have suspected that his prediction would be fulfilled in less than fifteen years. Yet on June 3l, 1929 he made his first public appearance with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. It was the start of a long and extremely fruitful collaboration, which ended abruptly with Van Beinum's sudden death in April 1959.

Eduard van Beinum was born in Arnhem on September 3, 1900. His was a musical family:

his grandfather conducted a military band and his father played the double bass in the local symphony orchestra, the Arnhemse Orkest-vereniging which later became the regional Gelders Orkest. Eduard's brother, Co van Beinum, was a violinist in the same orchestra and training to become a choirmaster. It was only natural that young Eduard should be groomed for a musical career. Encouraged by his brother, he began studying the violin and he soon took up the piano as well. Before long he proved himself an accomplished musician, and at sixteen played the viola in his father's orchestra. He graduated from the conservatoire with high honours and was soon much in demand as a pianist throughout the Netherlands.

The piano was not Van Beinum's only musical interest, however. From an early age he had been fascinated by the art of conducting. As a student at the Amsterdam conservatoire he already conducted amateur ensembles in Schiedam and Zutphen in a series of concerts which won general praise. He also found time to lead the choir of the church of St. Nicholas in Amsterdam, where he took profound pleasure in performing Gregorian chant. Working with amateur musicians, he thoroughly learned the ropes of the conducting profession, not least the psychological skills involved. In getting people of limited musical talent to perform to a high standard, he developed the tact and discretion he later used in building a cordial and fraternal relationship with the musicians of the Concertgebouw Orchestra.

It took some time for Van Beinum to decide what he wanted to do in music. His first love was the piano. He was by now a well-known soloist with plenty of engagements nation wide. He also loved to play chamber music. With his brother Co he had formed a violin-piano duo, performing regularly, and another such duo with his fiancée and later wife Sepha Jansen, a gifted violinist and a member of the Concertgebouw Orchestra, who often played as a soloist with the orchestra.

In the late summer of 1927 Van Beinum happened to read a newspaper advertisement inviting applicants for the post of conductor of the Haarlem Orchestral Society, the future Noordhollands Philharmonic Orchestra. Encouraged by his wife, Van Beinum promptly wrote to the orchestra, offering his services. After a trial direction he received the appointment and he made his debut with the orchestra on October 10, 1927. His handling of the orchestra at once impressed the musicians, the audience and the board. Very soon they saw in him the man who could take the Haarlem orchestra to a higher artistic plain. For this purpose Van Beinum was given an almost completely free hand. He was to he the orchestra's undisputed musical director. He introduced it to French music. Berlioz, Franck, Debussy, but also the new generation of French composers, including Ravel and Roussel, became regular fare, and Van Beinum succeeded in giving a brilliant account of this demanding repertoire. At the same time he championed the music of a new generation of Dutch composers. With works of such young composers as Willem Andriessen and Guillaume Landre' on the programme, the Haarlem orchestra soon earned itself a reputation as a "testing station for Dutch music".

As a result, Van Beinum not only achieved the ascent of the Haarlem orchestra to greater fame, but also the rapid rise of his own star as a conductor.

This rise did not go unnoticed in the wider world. From the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Van Beinum received an invitation to guest-conduct, and on 30 June 1929 he faced the famous Concertgebouw orchestra for the first time. He had fulfilled the promise he had made to his mother, fifteen years ago.

The invitation from the Concertgebouw Orchestra was indeed a great honour. The C.O. had been founded in 1888 as the resident orchestra of the then brand-new

Concertgebouw, and its first conductor was Willem Kes. Seven years later, in 1895, he was succeeded by Willem Mengelberg, who in a few years' time raised the orchestra to an unprecedented artistic level and made it take its place among the world's greatest. Foreign tours, gramophone recordings and radio broadcasts did much to spread the C.O.'s fame. By the time Van Beinum began to conduct the orchestra, its stature in the world was unchallenged. Van Beinum's first concert with the Concertgebouw Orchestra consisted of a performance of Haydn's Oxford Symphony, Rimsky-Korsakov's Piano Concerto and Saint-Saens's Third Symphony. The impression he left with this concert was a positive one, with the audience, but even more so with the orchestra's governors. He was invited to do more guest directions, even to conduct concerts in the orchestra's regular subscription series. Eventually he was given a permanent engagement. When the second conductor, Cornelis Dopper, left the orchestra, the choice of a successor was an obvious one.

For Van Beinum the appointment was a giant step ahead in his conducting career. But there were drawbacks. In Haarlem he had had a free hand in musical matters, deciding what was to he played and with whom. His position in Amsterdam was quite different. Here the great leader was Willem Mengelberg, who set out the orchestra's course with Pierre Monteux, and later Bruno Walter, at his side. The second conductor's role was confined to doing what he was told. In addition, his reception by the Amsterdam audience was one of cautious reserve. Van Beinum was not a powerful personality of Mengelberg's type. His ideal was to pay respect to the music and the musician. He tried to approach a score objectively and to present it in as honest a manner as possible. His attitude towards the orchestra served that purpose. Instead of making it subservient to his will, he tried to enlist the musicians' cooperation in rendering the composer's intentions as faithfully as they could. He occupied his place on the dais with modesty. For the orchestra, used to Mengelberg's often heavy-handed treatment, Van Beinum's direction came as a welcome relief. The idea that they were working with, not under, a conductor, gave the musicians a feeling of being respected and appreciated. They soon came to adore him. The audience, for the greater part, where less enamoured. Many saw his approach as superficial, even cavalier. "Van Beinum fails to captivate" was the verdict in one of the early reviews.

The new conductor had a hard time winning over his listeners to his way of music making. Gradually, however, he began to succeed. In those early years he applied himself to the music that was dearest to his heart, that of the contemporary French and Dutch composers, and Bruckner. The first concert he led in his function of second conductor, on 6 September 1931, included a performance of Bruckner's Eighth Symphony. It was to become one of Van Beinum's favourite works, which he often returned to and which he conducted as his personal testimony at his jubilee with the orchestra, 25 years later.

Even as second conductor Van Beinum managed to deploy his talent to the full. Over the years he received many attractive offers from other orchestras to become their principal conductor. When, in 1937, the Utrecht symphony orchestra asked him for this post, the Concertgebouw musicians, appalled at the prospect of losing their beloved Van Beinum, petitioned the orchestra's board of directors to prevent him from leaving.

Soon afterwards he received a similar offer from the Residentie Orchestra of The Hague. This offer was especially attractive, the Hague orchestra being generally considered to be the second best in the land. Van Beinum was severely tempted. The C.O. directors tried to avert the danger by appointing him" second principal conductor" next to Mengelberg. He accepted the appointment and thus was saved for Amsterdam. His first concert in his new capacity, on January 13,1938, was a festive occasion, more so because it premiered the Second Symphony of Hendrik Andriessen, Van Beinum's favourite Dutch composer. The appointment further enhanced his standing, singling him as the man eventually to succeed the ageing Willem Mengelberg.

The outbreak of World War Two threw all this in disarray. The German occupation profoundly affected all areas of life in the Netherlands, including the arts. The Nazis tried hard to reform Dutch society in their own standards. For the Concertgebouw Orchestra this meant that the music of entartete (degenerate) composers was banned, that Jewish musicians were to he sacked and that the orchestra's artistic policy was directly and indirectly determined by the conquerors. For Van Beinum hard times had begun. Willem Mengelberg sided with the Germans, a choice which permanently lost him his goodwill with the Dutch public. Van Beinum detested the Nazis and kept himself as aloof as he could, only giving info their demands if there was no way out. A few times he protested openly. He kept the concert season going as well as he could, while Mengelberg spent most of his time touring abroad. Despite these hard times, Van Beinum's popularity with the public and the orchestra still grew. After Holland's liberation in May 1945, the country could take stock of its conduct under five years of German rule. For the Concertgebouw Orchestra this process was particularly painful. Willem Mengelberg was convicted of having been a Nazi collaborator and sentenced to exile for six years. He died embittered at his chalet in Switzerland in the spring of 1051, just a few months before the end of his exile was due. Willem's cousin Rudolf Mengelberg, who was a director of the C.O. during the war, was suspended from his post. On review, two years later, he was fully rehabilitated. Of the 17 Jewish members of the orchestra 3 had died in the Holocaust - 14 went into hiding and survived the war - and had to he replaced. Other musicians were found guilty of collaboration and dismissed. They too had to he replaced. Van Beinum got off with an official reprimand. The verdict was that his wartime conduct, although less than firm at times, did not warrant a suspension.

The depth of the war trauma became once more apparent in the Spring of 1951, when Van Beinum was absent for health reasons and a replacement had to he found. For one of the scheduled concerts the C.O. engaged Paul van Kempen, a Dutchman who had assumed German nationality in 1932, before Hitler's accession to power. Emotions in the orchestra and the audience ran so high that the latter honed Van Kempen on his first night and the former refused to play under him on the second.