Willem Mengelberg Biography, part one

admittedly taken from: "Willem Mengelberg Dirigent Conductor", Haags Gemeente Museum, 1995. Frits Zwart

BACKGROUND AND EDUCATION

The parents of Willem Mengelberg, Friedrich Wilhelm Mengelberg and Helena Schrattenholz, both German by birth, established themselves with their atelier for church art in Utrecht in 1869. The immediate reason for their move to The Netherlands lay in the fact that Mengelberg senior had obtained the commission to make the church furniture for the Roman Catholic Cathedral in Utrecht after he had made the bishop's throne for the same cathedral in 1868. He equipped numberless churches in The Netherlands with furniture. The complete furniture of the St. Nicholas church in Jutphaas, designed by Alfred Tepe, came from the Mengelberg workshop. He also provided furniture for many other Roman Catholic churches including ones in Utrecht, Schalkwijk, Ijsselstein, Raalte, Abcoude, Arnhem, Kortenhoef, Houten, Mijdrecht, Workum and Amsterdam. Altar pieces were also made in the atelier for such churches as those in Zwolle, Amsterdam, Hilversum, Harlingen, Abcoude and Apeldoorn. In Germany, work from the Mengelberg workshop found its way to Bonn, Frankfurt am Main, Cologne, München-Gladbach, Paderborn and other places. For the cathedral in Cologne he fashioned work representations of the stations of the cross, the bronze doors for the North door and many other works of art, mostly church furniture. The increase in commissions for the work of Mengelberg was especially the result of the belief of the priest G.W. van Heukelum in the work of Mengelberg and in his artistic ideals. Van Heukelum acted as the unofficial adviser to the Bishop of Utrecht Mgr. A.I. Schaepman in matters of church art which naturally led to the work of Mengelberg coming to the attention of the bishop.

Willem Mengelberg. Lucerne 1895

On the 28th of March 1871, Willem (actually Joseph Wilhelm) Mengelberg was born in Utrecht. His parents were married on the 14th of February 1866. They had sixteen children, born between 1867 and 1890, eight sons and eight daughters, some of whom died young. Willem was the fourth child. Like his brothers and sisters he was initiated in the crafts practised in the father's atelier, but his natural musicality gained the upper hand. With time his parents recognised that a professional musical training was not to be avoided. Artistic talent can be observed throughout the family trees of both the parental families.

The foundation of Mengelberg's career was laid in the conservatory in Cologne. He developed as a talented and hard-working pupil. For his main subjects, he studied piano under Isidor Seiss (1840-1905), who in turn had studied with Friedrich Wieck, the father of Clara Schumann, and composition with Dr. Franz Wüllner (1832-1902). The latter was also his teacher for conducting and he studied music theory and composition with Gustav Jensen. Mengelberg's study was a great success and he completed the course with brilliant results for piano, composition and conducting. The commendations of his teachers Wüllner and Seiss are mainly in the direction of a career in piano playing. Later, Mengelberg declared: "I am much indebted to my teachers at the Cologne conservatory and if ever I became a good musician it is thanks to my teachers Franz Wülllner and Isidor Seiss [.. ], teachers of a rare quality with which one seldom meets".

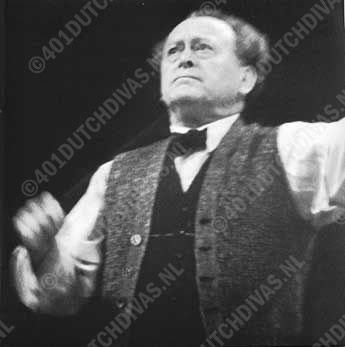

Willem Mengelberg, Berlin 1905

From 1892 onwards, Mengelberg worked in Lucerne where he could develop his many talents. There he conducted a choir and an orchestra, directed a music school, gave piano lessons and gave concerts with his ensembles. He even found time to devote to composition. In general one can say that his time in Lucerne was a busy one in which he gained valuable experience as a conductor, both choral and orchestral. The extent of his activities in the latter fields was nonetheless only of small demands in comparison with the work he was to do in Amsterdam. On average, in Lucerne, he conducted one orchestral concert a month. But the influence on his development for the future was of great importance, an importance he increased by his own curiosity to learn: "As a young choir-master in Lucerne then, I soon noticed that I could not demonstrate on various instruments and I immediately saw that this was an unacceptable problem. I then took lessons from all the musicians in order to learn the holds from them."

APPOINTMENT IN AMSTERDAM

In 1895, Mengelberg was presented with the honourable request to become conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam. This ensemble had been founded in 1888 and had acquired a good name under the conductor Willem Kes. Kes, however, had found an improved position in Scotland. Mengelberg came to stand before the Concertgebouw Orchestra as a young man of twenty-four. His first years in Amsterdam can not have always been easy for him. Complaints were made about his changing ideas about some scores, the members of the orchestra sometimes behaved in a difficult manner and his health was not everything it might have been. Yet Mengelberg's popularity grew steadily. In 1897 one of the critics of the Dutch press mentioned Mengelberg as "an artist of God's mercy". With his interpretations he managed to persuade his concert-going public and he succeeded in raising the level of the orchestra. Gradually, his musical gifts became recognised in The Netherlands and his position grew rapidly. He became conductor of the Diligentia concerts in The Hague, of the St. Cecilia Society and of the Philharmonic Choir in Amsterdam.

It was especially in his first years in Amsterdam that he sought the advice of his teacher Franz Wüllner. He was an influential interpreter of Beethoven because he had known Beethoven's friend and secretary Anton Schindler (1795-1864) well and had studied with him but had also known Schumann and Brahms well. It was no wonder that Wüllner's musical ideas were standards for Mengelberg and probably also for his fellow students. But Mengelberg also went to his former

teacher for advice on Bach interpretation. Wüllner could advice on tempos in such works as the Missa Solemnis of Beethoven, practical solutions for instrumentation in Bach's cantatas and for soloists for the St. Matthew Passion.

After working with the Concertgebouw Orchestra for a number of years, Mengelberg began to make a name and requests gradually came for him to be the guest conductor elsewhere. When the Concertgebouw Orchestra took part in the Strauss Festival in London in 1903, the Sunday Spectator remarked that it might have been better if Mengelberg had conducted more and Strauss less. Mengelberg received an important invitation to come to conduct the orchestra of the Philharmonic Society in New York in November 1905. After his performance the Musical Courier described his interpretation of Ein Heldenleben the best there was in New York at that moment, including that of Strauss himself. From that time onwards, the world stood open for him. He conducted for the first time in Paris in 1907 and in the same year he took on the position as conductor of the Frankfurter Museumsgesellschaft and a year later was given the directorship of a choir equivalent to the Philharmonic Choir in Amsterdam. In 1908 he conducted in Rome, from 1909 onwards for a number of years he conducted in Moscow and St. Petersburg, in 1910 he conducted in various Italian cities and in 1911 in London. However, because of his obligations in Amsterdam and Frankfurt, he had to refuse many invitations.

On many occasions Mengelberg was asked to be conductor or guest conductor of other orchestras. In 1910 an attempt was made to engage him as permanent conductor of the Philharmonic Society in New' York where Mahler then had a position. In general Mengelberg made high financial demands in such situations and commanded the salaries of other much asked-for conductors of the day such as Arthur Nikisch and Vladimir Safonoff.

In the period between 1921 and 1930 Mengelberg was working in New York for about half the concert season. He was able to train the combined former New York Philharmonic and National Symphony Orchestras to be a perfect ensemble. His spectacular recording of Ein Heldenleben by Richard Strauss with this orchestra in 1928 gives unequivocal evidence for this. From 1927 onwards, Toscanini was also conductor of this orchestra. It is worth noting that with the arrival of Toscanini, Mengelberg's programmes became increasingly adventurous. Yet already before Toscanini arrived, Mengelberg involved himself far more in the work of American composers than Toscanini was ever to do.

In New York Mengelberg gave 'Original Performances' of music by Kurt Atterberg, Nicolai Beresovski, Simon Bucharoff, Alfredo Casella, Gaspar Cassadó, Darius Milhaud, Ottorino Respighi, Ernest Schelling, Bernard Wagenaar and Emerson Withorne. Besides the tested symphonic repertoire he also presented many first performances in New Yorker or in America. Names of such composers as Ernst Bloch, James Dunn, Manuel de Falla, Pierre Ferroud, Paolo Gallico, Samuel Gardner, Heinrich Gebhard, Rubin Goldmark, Henry Hadley. Howard Hanson, Heinrich Kaminsky, Riccardo Pick-Mangialli, John Powell. Henri Rabaud, Lazare Saminsky, Karol Szymanowsky, Germaine Tailleferre, Alexandre Tansman, Deems Taylor, George Templeton-Strong and Hermann Hans Wetzler show that Mengelberg renewed the repertoire with a certain regularity over the years. Of course, Mengelberg also performed much of this repertoire in Amsterdam.

As a result of the unavoidable rivalry between the supporters of Mengelberg and Toscanini, Mengelberg left New York after a last performance with the New York orchestra in 1930. The proposed European concert tour of the orchestra of the Philharmonic Society for which Mengelberg had done so much for so long, was realised in that year. But it was Toscanini who could claim the crown of success because it was he who conducted all the concerts.

FRIENDS

It hardly need be said that many friendships grew up over the years with the musicians and composers with whom Mengelberg worked. Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, Alphons Diepenbrock, Ernest Schelling and Alexander Siloti are but a few of those friends. There were of course also many of those from the better circles of Amsterdam who liked to be considered a friend of Mengelberg. These were naturally mostly music lovers and the admirers of the conductor, and indeed Mengelberg kept up close relationships with many of them including Charles Boissevain (and his associates), Jo Beukers-Van Ogtrop and Ellie Bysterus Heemskerk, sometimes friends at first sight but above all friends for life.

Amongst these were also the governors of the Concertgebouw such as the members of the De Marez Oyens family, H. de Booy and R. van Rees.

The correspondence between Mahler and Mengelberg shows that it was not long after they had met at a professional level that they struck up a friendship. Mahler was very taken up with the lot of his Dutch colleague, whether it was to do with Mengelberg's success in America or with the final upshot of the famous Concert-gebouw conflict of 1903-1904. It is not seldom that through his letters Mahler's concern can be felt. He knew only too well how difficult it was as an orchestra conductor to get on from day to day with seventy or eighty musicians. Knowing of this feeling of comradeship it is amusing to read that Mahler was happy to take over the cellist Isaac Mossel in his Viennese orchestra. At the height of the conflict Mengelberg had demanded that Mossel be thrown out of the Concertgebouw Orchestra. Mahler was convinced that he could gain mastery over Mossel. There was also the friendship with Richard Strauss. Mengelberg inspired him with enthusiasm to collect glass and verre eglomisé and shared with him an interest in antiques and art.

As the years went by, Mengelberg developed a friendship with Alphons Diepen-brock that was fed by their common musical interests. Mengelberg very often performed Diepenbrock's music. But despite the fact that Diepenbrock could not initially get on so well with Mengelberg's personality, a personal relation did gradually grow. It was for the copper wedding of Willem and Tilly Mengelberg on the 5th of January 1913 that Diepenbrock composed the wedding song 'In the chilly, rough high North' with the text by J.Beukers.

Mengelberg was the conductor when the pianist Alexander Siloti, a pupil of Liszt, made his debut in The Netherlands in November 1897. When Mengelberg was engaged as guest conductor for a number of consecutive seasons in Russia, beginning in 1909, he performed in the series of Siloti and stayed at his home. Before and after this co-operation Siloti and Mengelberg regularly wrote to each other. Ernest Schelling was also a gifted pianist. He had studied with Paderevski and was frequently engaged by Mengelberg. This also led to a warm relationship. Like Mengelberg, Schelling had a country house in Switzerland where he enjoyed receiving his friends. Mengelberg was often his guest. He frequently conducted Schelling's music in Amsterdam and in New York.

A number of the members of the board of governors of the Concertgebouw who served a term of office during the period in which Mengelberg conducted there, can, without exaggeration, be counted amongst his most trusted friends. The Gedenkboek Mengelberg 1895-1920 contains various references to these friendships. It is clear that for many Mengelberg was not immediately an easy friend. Of the many Dutch friends a number are mentioned here who meant much to him and whose frienship lasted a number of years. Charles Boissevain was a member of the board of the Concertgebouw and one of the first friends of Mengelberg when he came to Amsterdam. Together with him and members of his family, Mengelberg would make excursions down to the Rhine valley in the quiet week before Easter when the performances of the St. Matthew Passion were done with. Mengelberg sometimes went on a cure with Boissevain in Karlsbad. Jo Beukers-Van Ogtrop was the president of the Philharmonic Choir in Amsterdam and a friend of both Willem and Tilly Mengelberg. She was a central figure in the Philharmonic Choir and was particularly instrumental in the organisation of the concert tours made by the choir and the Concertgebouw Orchestra to Brussels, Paris and elsewhere. Ellie Bysterus-Heemskerk also gradually meant more and more to Mengelberg and his wife. She was a violinist with the Concertgebouw Orchestra through which she got to know Mengelberg. Together with her mother she accompanied Mengelberg to America, already in the twenties. Later she was especially involved with the care of his scores. After Mengelberg's death in 1951 she was gradually given the responsibilitv for what was later to become the Mengelberg archive, a responsibilitv she undertook with considerable dedication. Like other friends, she was Mengelberg's guest at his 'Chasa Mengelberg' in Graubünden in Switzerland. An inscription on a photo of 'Chasa Mengelberg' written by Willem Mengelberg shows that he already counted her amongst his best friends in 1918: "To 'Aunt' Ellie Heemskerk, in memorv of Chasa M"' An illustration of Mengelberg's hospitality is given by the text written on another photo "To Aunt Ellie - 'work donkey' at the 'Chasa' from her thankful 'work horse' OH. 31st Aug.1922".

Chasa Mengelberg was the chalet which Mengelberg had built to his own design in Switzerland. The house was situated at an altitude of just over 7000 feet in the Swiss canton Graubünden. Mengelberg usually spent his holiday there between June and September. After a period of rest by himself he would receive his guests. The numerous guests once included Hendrik, the Prince Consort. The guests were expected to write something original in the guest book, on arrival or as they left. The first of these books was begun in 1914.